Happy Heat on SXSW

The first inkling something was amiss

came after my phone and email blew up on a Sunday morning. It was Louis Black, longtime friend, business partner and SXSW Co-Founder calling from Cape Cod, where he moved during the pandemic. “Alan, they think we’re doing a hit piece. I can’t be part of this … I need cover.” Then a couple days later the longtime CEO of SXSW, the guy who had the idea, Roland Swenson, tells me our call for submissions — written by one of our young guns, released via Instagram — is “vaguely threatening.” He cites this line:

We are especially interested in voices, communities, places, ideas, and dreams either omitted or marginalized by the standard narrative.

The whole thing catches me off guard because I’ve known these guys nearly 30 years and kinda believed I’d already passed the test. I consider SXSW one of the seminal experiences of my life, shaping both me and our city in profound ways. The event, objectively, is the product of genius.

And yet.

Change is afoot. The pandemic shut down the in-person gathering for two years. During that time, SXSW sold a controlling interest to an LA media mogul, the child of a billionaire. Co-Founder Louis Black cashed out, Co-Founder and CEO Roland Swenson moved from the day to day to Executive Chairman, and Co-Founder Nick Barbaro concentrates on the alternative weekly he founded with Louis, The Austin Chronicle. Also significant — after 15 years at the helm of SXSW Film and TV, influential programmer Janet Pierson turned it over to long time deputy Claudette Godfrey. Torches are being passed.

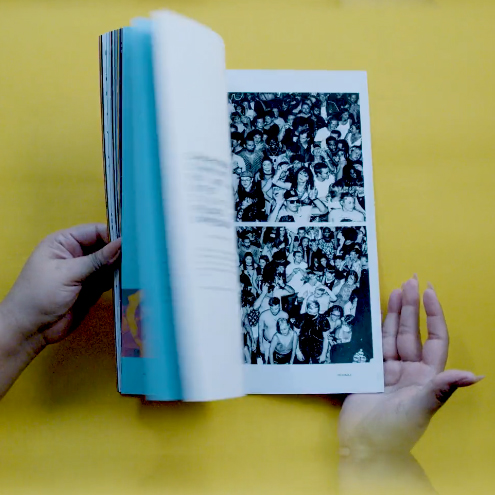

In an odd way things feel vulnerable. There are the little signs. Last year’s SXSW, the first in-person in three years, was small and intimate. Which made it a fantastic fest to work, like it was in the ’90s. You could park! No long lines! But Roland himself has been the first to say that smaller’s never better.

Fast forward to the now. The film distributor who lamented last year about the industry’s troubled state is sending one person. For three days. The colleague at an event planning company says past corporate clients are reporting back they’re either not attending or engaging in a more “intimate” way than they have in the past. The bottom line: a two year pause gave everyone a chance to measure. To assess. To spend that budget elsewhere and analyze whether the crowds and the cost of SXSW are worth it. In an AI-driven digital global multiverse, what’s the purpose now?

And yet.

Living in Austin has taught me two things: don’t bet against SXSW and don’t bet against Dell. I’ve watched both be declared dead more than once. 100,000-plus people are expected to descend the second week of March to chase the electricity that flows from the next. 2023 speakers include Tilda Swinton, William Shatner, #MeToo movement founder Tarana Burke, and General Motors CEO Mary Barra. Donald Glover will premiere his new series here, and as I write in early March new events are being announced every day. So maybe we all hold off on the premature obits.

And yet.

The city’s changed, the event’s changed, so what still works and what doesn’t? This question guided discussion with more than two dozen artists about a complex set of issues — the cost of living, the politics of storytelling, the way content is brought to market, and of course, the tense relationship with gatekeepers who attempt to monetize all this,

like SXSW.

When he looks at what he helped create, Louis is protective but resigned, concluding “There’s a new generation running things now. They’ll change everything and something magical will happen. But that doesn’t mean what we did

wasn’t cool.”

We couldn’t agree more.