Then and Now: The Evolution of SXSW Music

From Jackie Venson to Gretchen Phillips, multiple generations reflect on the SXSW music experience.

I pull up to Jackie Venson’s spot a bit drained until she opens the door and two wiener dogs jump for my legs. I reach out for one but before I can say a thing Jackie says she’s doing good, how are you? Better now, I respond and we kept moving towards the studio in the back.

She’s smoking weed and I’m moving too fast, stressed about framing her up, getting sound and juggling interview questions all at once, but as soon as I hit record, it’s like everything is exactly where it should be, because she just starts going, like she had been waiting for the chance to say her piece about SXSW.

“I think about it as a great way for Austin, Texas, to make a quarter to half billion dollars,” she says and pauses, as if waiting for me to say something.

“I just don’t think anybody talks about it objectively. I think everybody talks about it and what they want it to be, what they wish it was. I see it as a thing that brings money to the city. That’s it.” She takes a few breaths and continues.

“I see it as a way for bartenders to make a little extra money. Venues to make a little extra money. City tourism. And then when it’s over, it’s over. And then it’s going to happen next year, too.”

Her words echo off an altar of awards, books, and posters behind her with a force surely influenced by the online chatter surrounding us. Days prior The Union of Musicians & Allied Workers (UMAW) launched its “Fair Pay at SXSW” campaign, highlighting the gap between SXSW’s value and the way it’s been telling musicians to decide between a wristband to attend a festival or a $100 stipend for your set ($250 for bands.)

The call came just as I started my reporting for this story. I connected with close to 15 people from across the local music scene, hoping to deepen the conversation by exploring how the relationship between musicians and SXSW evolved with time.

FROM IOWA

TO AUSTIN

“It’s really weird,” Jackie Venson says as she sits back down in her seat after taking care of her dogs. “It’s like every city I go to, it’s the same conversation, like ‘Oh, my God did you hear the rent’s like $1,800 a month now?’ They were saying that in Des Moines, Iowa.”

This cross country dialogue about the city’s changing and culture dying is nothing new, but as I learned from Gloria Moore, Austin’s path there is rather unique. Moore was Austin’s Director of Tourism from 1984–1986, a time when she helped the city wake up to the potential of using music to attract visitors.

“I had noticed that all the economic development interest was in factories and industries and bringing things that could produce many jobs,” she says over the phone. “They really were not focusing on arts and culture at all.”

Moore heard something different, a growing music scene that no one was capitalizing on. “I was a real fan and I wondered why none of this was in our tourist brochures. We have the same potential as Nashville and New Orleans, and nobody is tapping into it.”

She’d go on to write “a nasty letter” to the state director of tourism but it caught the attention of Chamber of Commerce President Lee Cook, who called Moore in for a meeting, hired and tasked her with figuring out how Austin could replicate Nashville’s success in using its music scene to grow the city.

Moore decided to bring the business and creative leaders from the two cities together for a 1985 meeting that would change the trajectory of Austin’s music scene.

“The Bankers for Nashville explained to the Austin bankers how you collateralize music,” remembers Linda Lewis, political action chair of the Waco NAACP, who attended the meeting as staffer on behalf of Governor Mark White. “She and Lee Cook, they really initiated that whole idea of Austin as the third coast.”

Part of the return on collateralizing music were initiatives like the Hotel Occupancy Tax (HOT), which attempts to reconcile an otherwise paradoxical relationship: using music to grow a city while acknowledging that growth ultimately prices out many in that very culture.

In 1990, a portion of the tax was allocated to Austin’s live music scene. However, Gloria notes that a constitutional amendment strictly defined the tax, limiting its use to events and initiatives that definitively promoted tourism. Even though the money was earmarked for the arts, the goal was growth.

“Unfortunately it is a paradox and I don’t know that there is a balance,” says Moore. “That money does fund a lot of the cultural enrichment that the local citizens enjoy. But no one from out of town comes to a small play at Hyde Park Theater.”

“The wheels started turning,” she continues. “The money side of it came to see it not as an art, but as just another new form of entertainment, a new sector of the economy like technology.”

“I’ll never forget how thrilled Lucinda Williams was to get $50 in cash to play,” she goes on. “We would put travel writers and reporters on the Austin Paddle Wheeler that circles around Town Lake, and we would book her for entertainment. A few days later we would have people calling, saying, ‘I read about the Austin music scene in the Des Moines Register.’”

In a world where putting butts in the bed was the main objective, Gloria’s plan was working.

They started thinking bigger. What if Austin had an event like CMJ or the New Music Seminar? Something to leverage the new convention center and simultaneously bring people to the city.

“Well, about that same time, the guys from the Austin Chronicle came to the Chamber of Commerce to the convention Bureau, and told us they were starting one,” recalls Moore.

The timing couldn’t have been better for the Chronicle proposal. “That’s exactly what we wanted to do with the directive. The Chamber of Commerce gave them a $10,000 grant.”

“Everybody wanted Austin to be recognized,” remembers Joe Nick Patoski, Austin writer and Austin cultural historian. “Roland, Nick, and Louis, were all about that. We want to show it off. We’re proud of what we’ve got, and we want to share it.”

And it all fell in line. Moore says Austin was on its way to becoming the next New Orleans, but that didn’t cross their minds at the time. “No one ever, ever anticipated it going over the edge in the early days, we were too thrilled just developing it.”

SMALL POND

“I loved the hell out of South by Southwest in the beginning,” remembers Gretchen Phillips, Austin’s seminal lezzie rock icon. “It was a lot of fun to have my friends from New York visit and get to show them around town, this unimaginable version of Austin.”

This new place has become too much for Gretchen. In 2014 she moved to Canada, citing the erosion of what once was a sacred pond. “There’s a massive dilution, you know, it’s taking place,” she says of Austin now. “And that’s just going to be the nature of, you know, a town being attractive to a variety of humans.”

These days she’s back in town, but only for a stint, in part for SXSW but more so for old band Meat Joy. In May they’re getting back together for the first time since 1985, the start of rehearsals for reunion gigs in the fall. But in 1987, her other group Two Nice Girls were the talk of the town, a chatter that led to an invite to play one of the first ever SXSW music showcases.

“We were actually very skeptical,” says Phillips of the initial offer they received to play. It was low, too low. “At the time we were making plenty of money from our shows, so why would we do this?”

But then they saw it’d be at Hole in The Wall, a spot Gretchen loved but hadn’t played yet. Plus they’d be sharing the bill with The Wagoneeers, a local band doing “a twangy, somewhat country-ish thing.” That and a little convincing from SXSW Co-Founder Louis Black was all they needed. Forgoing payment for badges, they got an experience.

“A mom became outraged at the drummer who was going out with her daughter, and there was a bit of a scene out of a movie,” Phillips remembers. “He was a really handsome devil, so there was drama, which was fantastic. I loved seeing that at The Hole in the Wall.”

When they got off the stage they met a New York dude named Jim Fouratte who wanted to be their manager. The thought of big-time city help like that was exciting so they passed him some tapes and he passed them to Rough Trade who ended up signing Two Nice Girls.

“Despite my reticence, the experience of doing it was pretty cool,” reflects Phillps.

SO CLOSE BUT

YET SO FAR

SXSW could feel a little magical, but for those east of I-35, it could also feel very remote. Because to get an opportunity, first you had to get on stage.

“It was white, it was for the white community,” says Brenda Malik on her first impressions of SXSW. Malik, an Austin resident since 1958, grew up across the street from the Harlem Theatre on 12th street before moving to the historic Rogers-Washington Holy Cross Neighborhood where she still resides today.

Malik was determined to be on television after not seeing anyone who looked like her on screen as a child. She became Austin’s first black woman to anchor the news, holding the desk at both the CBS and NBC Austin affiliate stations, while still living within the indie media world of the Chronicle boys, Gloria Moore, and Linda Lewis.

“I contacted them and asked if they were doing anything on the east side of I-35 and they weren’t,” remembers Malik. “It was using city resources, so we felt like we needed to be part of it.” Lewis and Malik would go on to form Light Years Ahead, a production company initially focused on creating black programming for SXSW and the greater Austin community.

“We wanted to highlight the gospel influence in the black community,” says Malik. In 1991 Light Years Ahead was tasked with creating a SXSW official gospel showcase in East Austin.

But both Lewis and Malik say the program was not well promoted or publicized, and that local talent was largely bypassed, mirroring the larger segregation of Austin at that time. “We wanted them to use that as an initial delve into the black community, but they didn’t take the hint,” says Malik.

“It was a good first step,” says Linda Lewis. “But the word I’m looking for is synergy.”

SXSW OF THE SPECTACLE

“I call them equity hurdles,” says Jackie Venson when I ask if SXSW’s become more inclusive since those early days. “It’s like, ‘Oh, South by Southwest, you get all these opportunities, and it’s this big discovery thing, and you know, it might change your life, and the best of the best get it,’” she pauses to crouch in her seat, “but you’ve got to pay to get a chance.”

In June of 2020, Venson got the Austin music community thinking about representation vs. reality when she sent off a series of tweets pointing to the absence of black musicians at Blues on The Green, a local summer concert series, and within Austin media as a whole.

Her tweets led to a shift. She says she’s noticed more diversity on lineups and in coverage of the scene as a whole, but with SXSW, she can’t really get past how the fest is handling artists.

‘I’ve been watching that happen for my whole life, like my literal whole life that I’ve grown up in this city,’ she said. ‘So all the people on top are just like ‘Mum’s the word,’ and all the people underneath them are like, ‘Hello!!!!?? Do you hear me?’”

The dogs scratch at the door as Jackie lets them out, and we take a break. When she returns, she softens her tone. “I don’t want to step on anybody’s work,” she says. “There are a lot of people who are working hard to change these things. People here care more than usual.”

I feel that when I enter the home of Omar Lozano a few days later. This year Omar will be an official SXSW artist for the second consecutive year. He’ll be performing under Trucha Soul, a label he started as one of the only Latinx-owned and Latinx-focused vinyl imprints in the industry. They collaborate with artists from Texas and Mexico, and their live experience serves as a community touchstone inspired by Sonidero Sound system culture. From growing up in section 8 housing in El Paso to teaching himself how to mix in his closet, as Omar grew up, SXSW remained a goal.

“I remember being drawn to that idea of, you know, music being ubiquitous in a space,” Lozano says from in front of a massive record collection housed in his East Austin home. “We’d sleep like five or six of us in the friends you know little apartment with like less than $100 for the week.”

Those years proved formative to his path, one that’d take him back to El Paso to create DIY spaces to explore and present left-of-the-dial cumbia and experimental electronic music. Soon he was coming back to SXSW with more of an identity, and an intention, and went on to produce some of the biggest unofficial events in the city. Accessibility was always the goal.

“I went from understanding all those barriers to me as a fan, specifically being underage and super poor. It was like, well, what are the opportunities that we could do, touchpoints for those audiences?” he says.

He answers his own question as he talks.

“Leveling the playing field in an unofficial way through large-scale events was my answer to a lot of that,” he says. “Low-cost entry barriers, to me, are the heart of Austin. Whether that’s unofficial South by events, a tunnel rave, a house party, or a co-op, the unofficial stuff had a much greater impact on the ways that I became involved in live music.”

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the shift to DIY coincided with the rise of corporate sponsorship, turning the festival more and more into a branded experience. But it worked for the times. Back then there still was a synergy between the experience SXSW promised — a feeling of discovery, possibility, and connection — and the early ideals of social media.

Ian Orth was right in the middle of it. The managing partner and creative director of local concert booking company Resound Presents who also helps run venues like Mohawk and Parish, Orth says he hasn’t missed a SXSW since 1994, when he convinced his teacher to let him cover the music festival “from a high school angle.”

Next thing he knew, he was interviewing Beck and getting backstage passes to the Tony Bennet show. Orth would move away for college but returned to Austin in ’04 and started throwing dancing parties. In 2007, he teamed up with friends doing the same in New York and Philly to throw a DIY SXSW shindig at a friend’s house in East Austin. They got a couple of kegs and made a booth out of the washer and dryer and Simian Mobile Disco, Boys Noise and Diplo spun all afternoon.

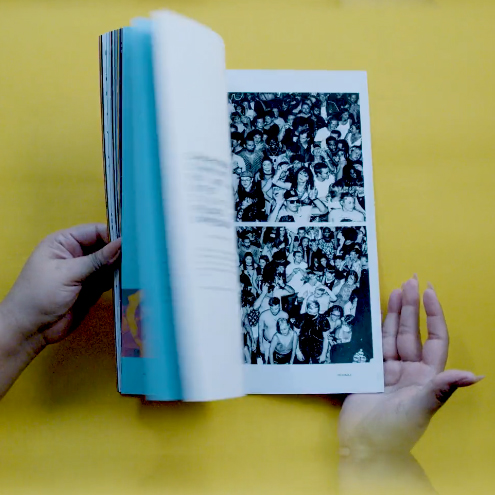

-2.jpg)

-.jpg)

“That era of South by from 2006 until 2014 when the accident happened, that was such a wild time,” says Orth. “You’re at this crux of youth marketing that was still a no man’s land, social media was just being born, it was like the MySpace age,” he says of the mid 2000s experience. “Sparks energy drink was everywhere, renegade parties were everywhere. So many unofficial and obscene things went down. The party to go was the Vice Party, and the conversation all week was ‘do you have the connection for the Vice party?’ It was blog house heaven.”

As the ethos of SXSW shifted from bands to brands, artists became disillusioned with the official experience.

“I was in a band that played multiple official South by’s. It was miserable,” says Orth. “You get to these shows and no one is into it, no one’s watching the band. Your average music fan is not interested in coming to a music industry party.”

While early SXSW may also have fit in a world where gatekeeping was still in the hands of the labels and industry, the weight of that cosign fell with the rise of the web, and the distinction between official or unofficial faded with it.

“I got rejected three times in a row. And then when I finally did get accepted, my showcase had ten people at it,” says Venson. “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard that story.”

Alex Peterson of local band Alexalone had similar thoughts. “Last year, we didn’t even apply and it was past the deadline and then we were just like, we’re going to play the show, we played our label showcase Polyvinyl Records and they were just able to waive our application fee, and we’re just like ‘we’re South by official now,’ it just felt arbitrary,’” says Peterson in a Zoom interview with bandmate, Drewsky Hullet.

“It feels very much like the positive things that do happen are squarely within the unofficial DIY side of things,” adds Hullet.

After that random official showcase last year, the two say Alexalone are keeping things light this year with only one unofficial show planned for the boundary-pushing DIY art space in town, All the Sudden.

You might think they’d have more in store considering prior cosigns from NPR and The Austin Music Awards, and that Peterson also tours with Hovvdy, but Peterson says their relationship with the festival has shifted since their early years when it was “just a clusterfuck, like my chaos week.” Back then they were taking gigs in front of Banh Mi shops on South Congress. “Taylor Hawkins of the Foo Fighters walked by, watched a few songs,” remembers Peterson. “But then he just kept walking.”

“It’s just a weird, like, little universe in itself, it feels like things can happen but that whole feeling, it’s really easy to take advantage of people when everyone’s super excited about what may or may not happen,” they continue. After those early years hawking over the lineup and scheduling out what sets to see between their own, SXSW became more about the opportunity to cultivate relationships around music.

“I feel like I just met a lot of friends,” Peterson responds when I ask if they ever really connected with industry folks at SXSW.

“It doesn’t really feel like it has much to do with the festival itself. It’s just that bands come to the festival,” adds Hullet. “I just wish everything would be a lot more apparent,” he says. “Stop selling the idea of exposure, and instead be like ‘hey, come to us and there’s going to be a lot of parties.’”

Alex and I giggle at his comment because it feels so on the nose. Outside of music, SXSW is an opportunity to party and profit on the visiting corporation’s expense, making a gig paying around 100 bucks a little less practical.

“When you have someone in your band, that’s when they make their money for the year. It’s kind of hard to say, ‘You want to play a million shows and not make any money this week?’” says Peterson, discussing the challenges of balancing potential SXSW gig opportunities with the chance to earn a freelance paycheck doing creative work for brands elsewhere during the week. Last year Drewsky got a grand for mic’ing up Lizzo for an hour interview. Moreover, the festival has long surpassed its origins as a way of connecting locals with the industry.

“If you are a band from Austin, SXSW is not your big break,” says Orth. “People are coming here to make and finalize deals that they’ve been working on all year long, and then they’ll see upper echelon indie artists coming in from out of town. No one is coming to see TC Superstar.”

Orth sees value in the way the festival helps the local scene book out for the rest of the year. “We need it because it’s an opportunity for us to get our company in front of many of the booking agents we work with year-round,” he says. “About 80% of the booking agents we use to book our tours are typically present at SXSW. That’s a crucial aspect of our business.”

With all that in mind, I asked Orth to summarize the trajectory of SXSW music since the mid-2000s.

“The major decline of South by pre-2020 really started in 2010 and 2011, as so much money was being thrown at the festival and it became too big for itself. It was a really special moment and it had evolved into this sort of corporate monstrosity where the focus was on spending money to get in front of people. But, the culture shifted towards a dark place, and it came to a head with the 2014 accident, which was the breaking point. For me personally, that’s when I realized that this wasn’t that special thing that I had found when I was 14, where I could go and find out about authentic emerging artists. That’s not there anymore.”

In 2014, during a Tyler, The Creator performance at South by, a drunk driver crashed into a crowd of people waiting outside the venue, killing four and injuring dozens.

WHERE'S THE

MUSIC?

If the official experience is mostly about making deals now, imagine it without music. Tech folks walking around with no soundtrack to blow off the networking steam.

“The only reason the festival works is because there’s a bunch of bands, the musicians are making this thing fun and cool,” says Hullet. “Even though we have this tech moment at the beginning, that’s really where all the money is, just it makes no sense that, like, none of the money ends up in the pockets of the artists.”

“I do think that the networking thing is real in a way, but it just comes down to can you even afford to be here,” adds Peterson. “I think a lot of people burn themselves out because they’re doing all this work for no money. I think that’s the sad thing and that’s the thing that South by perpetuates.”

This question, who can afford to be here, is at the heart of UMAW’s inquiry into SXSW. They’re highlighting the impracticality of the experience for indie musicians. UMAW says in 2022, SXSW made $275,055 in musician application fees alone and they’re still set on not raising band payments, even after the recent buy-in from Penske Media, a multi-million dollar corporation that already owns Rolling Stone, Variety, Billboard, and The Hollywood Reporter and more.

“We got a lot of bands writing us about having breakdowns in the middle of South by, you know, lugging their gear in between all the shows they’re playing for free while also paying $400 a night to fit all of their band in a single bed hotel room,” says UMAW part-founder Joey DeFranceso. “The industry still convinces musicians that it you’ve just got to suck it up and go do it, because it is going to pay off in the long term.”

DeFranceso says this isn’t the first time UMAW has probed SXSW. In 2017, they successfully campaigned for the festival to change its visa policy for international artists who were required to enter the US on a visa waiver program that prohibited payment for performances. UMAW’s efforts resulted in a change of policy by SXSW, allowing international artists to obtain the appropriate work visas to participate and receive payment for their performances. Then the pandemic gave everyone more time to address other discrepancies, a process that led them back to SXSW.

“Musicians haven’t been organized like they are now,” says DeFranceso. “We haven’t been able to get together with the collective voice and say no.” Their petition demands SXSW increase pay to at least $750 for performing artists, provide festival wristbands for performers, and waive the application fee. As of early March, 2,126 artists have signed the petition with 160 of those local bands.

“If you want to just objectively do better, this is the easiest place to start,” says Jackie Venson on removing the application fee, the first step to improve conditions for musicians at SXSW. “Then double the pay.” Venson goes on to wonder how SXSW defines merit and how that process could be less partial to bands with resources. She says it could start with asking less bands to participate. “More bands getting less is a manipulation, as in taking advantage of, less bands getting more is more of a due process, you know what I mean?”

Venson says this might entail a more rigorous application process that evaluates bands holistically rather than online metrics, with consideration given to whether the opportunity is beneficial for the band at their current stage. That way bands aren’t dropping their last few grand on a trip to Austin that only results in an official showcase for three people in the crowd.

“There has to be some consideration of whether you’re not developed enough to do this yet or you are too developed and you don’t need this, so we’re going to keep this to somebody else who could use it more,” she says. “Maybe it’ll be a harder festival to get into…if that means each band that gets into it is treated better. Yes, that’s how you handle volume.”

The process could help SXSW return to its roots. “Could be a really cool place for the industry to kind of restart, “ Venson says. “It would actually make South by Southwest go back to its original music discovery kind of thing.”

Venson wasn’t the only one who thought a better SXSW starts with reorienting the festival around musicians. But for that to happen, she says you’d “need a whole team,” and a big part of that team should be local representation, “More like local representation of artists working for them,” says Hullet.

It seems like a good idea, and something I was going to just leave in as merely a suggestion until I connect with local artist Yvonne Goodwyne, who releases dreamy music under Vonne. They’re taking me through some of their SXSW memories, like the sweaty parties Hikes used to throw in West Campus, but it’s not until halfway through our interview that I realize that Yvonne is the person Dreswksy wishes worked at SXSW.

“I have to say that I actually work at South by right now,” they say before specifying that they have to keep the particulars of South By’s selection process under wraps. The fact they’re in the room is encouraging, but they can only do so much, “I will say I don’t have a lot of power.”

The whole thing has me thinking back to something Alex said a few days before. “They’re so many cool people who work at South by, but it’s like, who has the power to make change?”

Those in the offices making deals, you’d think, so I was curious to ask Ian Orth how the festival is being discussed ahead of what promises to be its biggest edition since the pandemic.

“People are still trying to reset from 2020, creative thinking is not at the top of people’s minds,” says Orth. “From a lot of the meetings I’ve been in this year leading up to South by, it’s so many of the similar conversations that we were having pre-pandemic. Conversations that are like ‘How do we restore this? How do we return to the way things were?’ rather than ‘What can we do that’s entirely different?’”

To Orth, the focus should be on the artists.

“In all the conversations about Austin and SXSW changing, there’s one constant and that’s the fucking artists,” he says towards the end of our call. “South by has more work to do to repurpose itself for the artists than artists do repurposing themselves for South by.”

“At the end of the day, do I think that’s going to happen? Music I think is very obviously a leading component for South by, but they need to make money.”

“The Penske group would not have bought it if they didn’t see potential to grow it even more and increase revenues,” says Joe Nick Patoski before citing their announcement of SXSW Australia,” set to debut later this year.

THROUGH

PEARL'S EYES

“There are a lot of nice people,” begins Alex Peterson. “When so many of them show up in Austin like that still feels like a miracle. Despite, like, despite all of the…despite everything.”

Alex thinking about SXSW so miraculously now has me thinking about the whole thing more theoretically, which brings me back to Omar.

“The only way that you have a place is like, you have not only like a legacy, but also a continuation of those stories and those spaces,” he says. “And, we know in Austin it’s hard to maintain space right now, like not just physical brick and mortar space, but even more like metaphysical community space because of the development of the city.”

“What helps us is, how are we using these opportunities that we have now and spaces that we have now?”

Omar’s perspective has me thinking about how SXSW fits into the larger tug and pull characterizing Austin’s cultural history, a balance of trying to preserve local culture while maintaining the essence of what made it unique in the first place. Infuisng meaning into the spaces we have left gives us a semblance of agency, a vision exemplified in the way the kids are seeing things down on Pearl Street.

I’m a little late arriving thanks to this self-driving robot going 10 down Nueces. I’m at Pearl to see the South by through the eyes of moonbby6, who books shows for Pearl and runs meme accounts like worm trip in her free time. She’s pacing back and forth, worried this weekend’s show might get canceled by “the office.”

We find a place to sit down and she grabs two frequent chillers, Malik and Dillon. They talk under Talyor Nelsons’ Wall of Chill; a mural of the Austin skyline from around ‘03 in the center of a yellow and teal eyeball.

“Fucking music, dude, music,” Malik says on how he ended up in Austin. He’s gotta be close to seven feet tall and seems to be nowhere near college-aged.

“We lived in a fucking RV, like in New York in a parking garage, trying to make that shit fit wherever it could and I’m like I’m over it and I just jump on the back of a train dude, jumped on the back of a coal train, to Tusla Oklahoma, a few truckers, picked me up droved me all the way down to Austin.”

He speaks with this spontaneous tone, saying surprising things as if they were natural, similiar to the way moonbby6 describes how Stevie Ray Vaughan played there once or how she speaks on Bart’s landing, this wooden structure by the pool made by this dude named Bart who showed up asking to live there with only wood to his name. “He talked to the people who owned the place and was like, Can I just build this structure and live here?” And they’re like, “Yeah, sure.”

Dillon doesn’t sound surprised either.

“Legends have played here before and legends will play here, eventually,” he says definitively before getting more emotional describing his experience playing Pearl with his band Grocery Bag.”

“It’s so raw,” he says as his eyes light up behind thick black rimmed glasses. “Where else are you going to experience that much chaos, can’t see anything, lights everywhere, all you hear is like a snare in your left ear, I mean, getting to play here is crazy because it’s THE SPOT, the show spot. If you say I’ve played Pearl before, it’s a resume item.”

“Crazy story for me,” starts Malik, “I think it was the South by-”

“Wait don’t say South by,” interjects moonbby6.

“Spring break party, yeah…”

They go on to tell me about how last year, they had a band from the UK come through - a squad of six or seven with nowhere to stay. They asked moonbby6 if they could stay at Pearl, and in exchange they’d play the party. An easy call. “Dude of course” moonbby6 told them, “it’s a college living place.”

“It was so humid everyone was dripping sweat,” remembers moonbby6. “The ceiling was leaking but it was cool because all the performers were being all dramatic with the water.”

The magnitude of the moment hit when they heard the band on BBC radio saying their favorite experience in Austin was at Pearl. “They were used to playing for way bigger crowds, and they were saying it was cool to connect with a crowd of people who were just obviously there to enjoy themselves, for the music and not necessarily, for networking or trying to, I dunno, do something more serious,” she says.

“There was a dude doing calisthenics in the pit,” adds Dillon.

“I walked up the little stairs over there and someone had a notebook out with their pencil, just drawing everything that was happening,” adds moonbby6.

There’s talk that either Pearl or 21st is getting bulldozed, and a look around West Campus, filled with construction cranes, feels like just a question of when. “This is kind of hard to replicate, says moonby6. “If you think about it, like, you can say there’s another Pearl, but it’ll never be this.”

Saturday comes around, the day Pearl’s scheduled to throw a party featuring drag, jazz, dj’s and more in a party dubbed “punk prohibition.” I’m planning on checking it out just to see how moonbby6’s mind works but as I’m on my way I see her Story, “Don’t come, the party got shut down,” she yells over a blaring alarm.